Shaman at a Psychiatric Ward – a Conversation with Phil Borges

A conversation with Phil Borges, film director, photographer, and traveller. How do cultures outside of the Western world approach mental illness and its healing?

Paweł Franczak: You have travelled the world in order to study and document primitive cultures, including their approach to mental illness, which they often consider as a vital breakthrough point, rather than pathology. What is your personal take on this attitude to mental disease?

Phil Borges: During my documentary work in various parts of the world, from the Amazonian Forest all the way through to Siberia, it often struck me that these cultures offer a completely different narrative of the mental crisis. In a majority of world communities these episodes, rather than being treated as a symptom of a brain disease, are perceived as indicating this person’s extreme sensitivity, which can usefully serve the entire community. Having noticed this attitude, I started to think about our own paradigm of the mental illness, which I consider to be causing a lot of harm. If a young person, in the midst of a mental crisis, hears that their brain is diseased and that there is no known remedy, this must be a horrible, devastating experience. Most mental illness is accompanied by a terrible fear, yet it is extremely easy to label a person as someone who should be isolated, because he or she is „ill” or „does not belong to the normal human race.” This means stigmatization and marginalization. We encounter a person who is in crisis, and we enhance the fear they are already feeling, shame them and make them feel powerless. At the same time, it has yet to be proven that the chemistry of a brain during mental crisis or even a psychotic episode is any different from that of a „healthy” individual.

But what about drugs that are used in order to regulate dopamine levels in the brain?

It is true that antipsychotic medication affects the level of dopamine and serotonin in the brain. This does not, however, necessarily mean that the crisis was set off by divergent levels of these hormones. We should look elsewhere, as the element that has caused the crisis may have been extremely important, as a starting point of a major transformation with a positive overall outcome. If we limit our response to a mental crisis to a dopamine-enhancing drug prescription, we may stop this broader, more important process.

At the same time, you are warning against the romanticising of altered states of the psyche and tribal methods. Can you tell me why?

The reason is simple: not every person with the experience of a mental crisis will become a shaman. Myself, I am far from this romantic take on the altered states of our psyche. I also need to stress that I am convinced that medical drugs do have their rightful place in our world. If a person’s condition is very severe, it exactly the pharmaceutical products that can help. The problem is that we tend to see them as a long-term solution, rather than something that can help during an acute crisis. Medication is not a solution in the long term, due to its side-effects and because it does not go to the root cause of the existing problems.

You directed „Crazywise,” a documentary whose main character, Adam, was prescribed one drug after another, each of them having significant side-effects. The doctors followed the standard procedure, where they would simply state: „This drug does not seem to be working? Ok, then, let us try another one.” What would have been happening to Adam, had he been born in Nepal, or in any other country that you visited with your camera?

First of all, perhaps he would not have been going through this mental crisis at all. Our society is extremely individualistic and geared towards increasingly fierce competition, even amongst very young children. The suicide factors amongst school children and youth are getting higher and higher. In the US, people find it increasingly difficult to attain middle-class living standards. Competition is ruthless and some people simply cannot stand this pressure. As for Adam, he did not get good grades at school, but was a promising sportsman. This made him think of becoming a professional and earning his life this way. As it turned out, this level of competitiveness was extremely hard for him to sustain. I believe this was when his depression started. Adam is an extremely sensitive person, full of compassion and empathy for others’ emotions. In a culture that values such a sensitivity, where altered states of the mind are understood or perhaps even appreciated, he would have been free from most of the fears that were too hard for him to endure in the Western world.

Even if not everyone becomes a shaman following a mental breakdown, anthropologists tell us that in the Siberian and Asian cultures this is frequently a rite of passage in the making of a healer. Our culture sees breakdown as an unwanted incident and tries to suppress its symptoms. Why would that be?

Because in our culture there is usually no-one who could take care of a person in crisis and lead them down a path of healing, other than psychiatric care. Let me give you an example. Each year, fifty thousand persons in the US die following an overdose of simple painkillers. This, in a way, signals the very same problem: people take medication so as to avoid the emotional pain associated with looking deeper inside of their own psyche. Some psychiatrists are doing a great job, however, a quick fix, which is a drug prescription, remains a temptation, as opposed to the slow process of being with the patients and giving them long-term support, involving more than just one helper and covering the social networks of the patient.

Cultural differences also translate into the nature of symptoms. Auditory hallucinations, also known as “hearing voices ”, are the experience of several to over a dozen percent of humans. It is only in the US that these voices are usually harsh, critical and threatening, while in India or in Africa they tend to be rather kind. What is the reason behind these differences?

I am personally familiar with people living in the US who hear voices, who told me how their nature changed over time. Friendly and helpful at first, they would become malicious when the person hearing them started to worry about them or suspect that they might herald an illness. Adam, the main personage of my documentary, was at some point in time taking more than a dozen different medications, many of them meant to alleviate side-effects of others. This made me think of a laboratory rat! Now, if we treat the crisis as a portal, a gateway that the person needs to go through, if we approach the process in a positive vein, the context turns positive and supportive. “Yes, it is true, you are going through a pretty rough time, but chances are that you will emerge stronger, and live at a different level.” It really does matter to make sense of what the patient is living through!

In the rich Western world, the efficacy of psychiatric treatment reaches 30 percent, in spite of antidepressants and anti-psychotic medication being prescribed at unprecedented rates. Is there no way out?

Luckily, also in the so-called West we do have success stories. In a small town of Tornio, located in Finland, just by the polar circle, the psychiatric ward of the local hospital decided to carry out an experiment. Whenever a person experiences a mental crisis, a team goes out to meet them, as well as their family, partners, friends, employer – anyone who matters to them and is a part of their social network. They open a discussion during which everyone is free to share their feelings, for instance say that they find the situation scary or feel uneasy about it. For the team, the crisis “belongs” to the entire group, rather than to a single person. They abstain from a clinical assessment of the situation and do not use labels; clinical diagnostic, if it is carried out, serves exclusively the purposes of the health insurance. This Open Dialogue method is gaining popularity in various parts of the world.

It has also become known in Poland, where the so-called “Healing Assistants”, i.e. persons who have been through a mental crisis and also received appropriate training, already work in Mental Health Centres, helping others. Does this give some hope to us, Europeans?

Yes, definitely. I have conducted numerous interviews with persons who have been successful in surviving altered mental states and they all told me the same thing. First, we needed to know if there is a chance that we can heal, yet there was no-one who would reassure us in this way. Second, we wanted to have the support of persons who have been through the very same thing, rather than those who have merely read or head about it. Third, we needed to make sense of what was happening to us. Sadly, many of these patients would be told that they suffer from a strange and incurable illness, due to their genetic heritage or to a sudden, mysterious alteration of chemicals in their brain. Let us also not forget that the Finnish team based in Tornio was also subject to criticism. It was said that their methods were not proven and did not carry sufficient research documentation. Nevertheless, over the period of thirty years, they have managed to move the schizophrenia rates in Finland from the top of the European list right to its bottom!

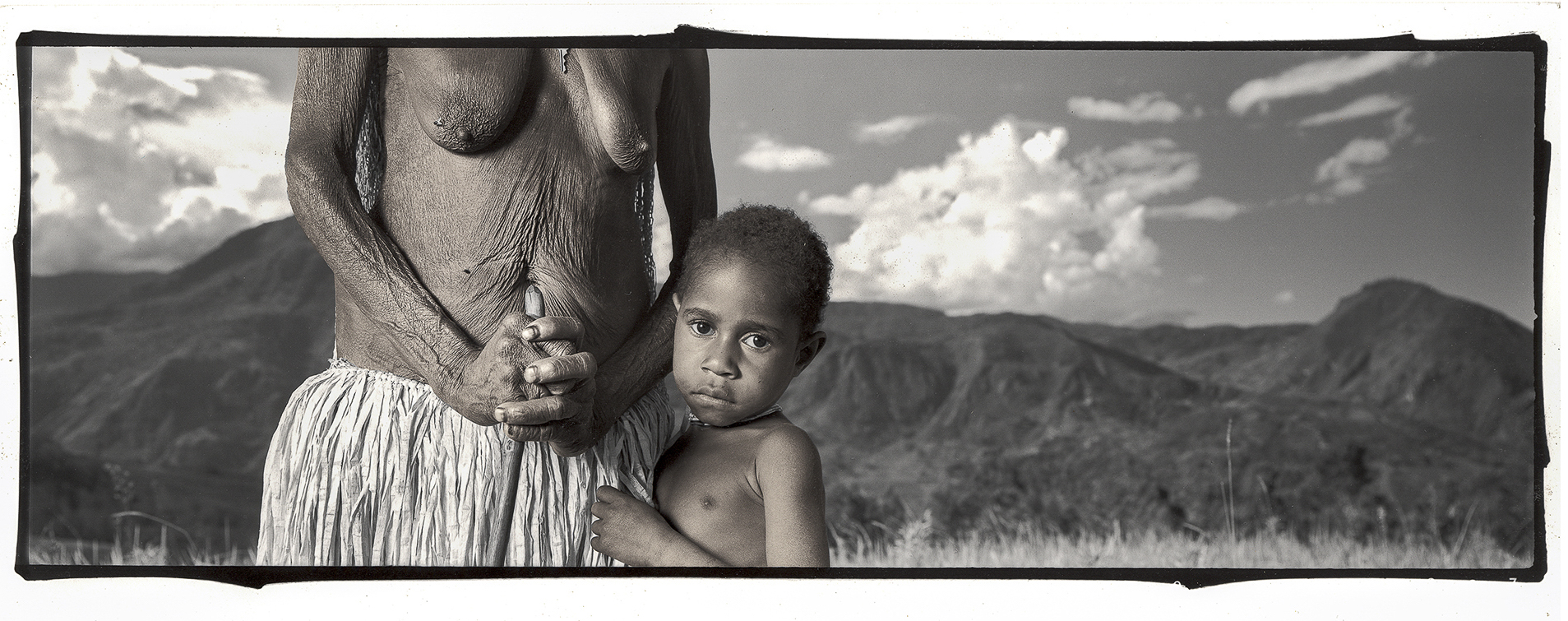

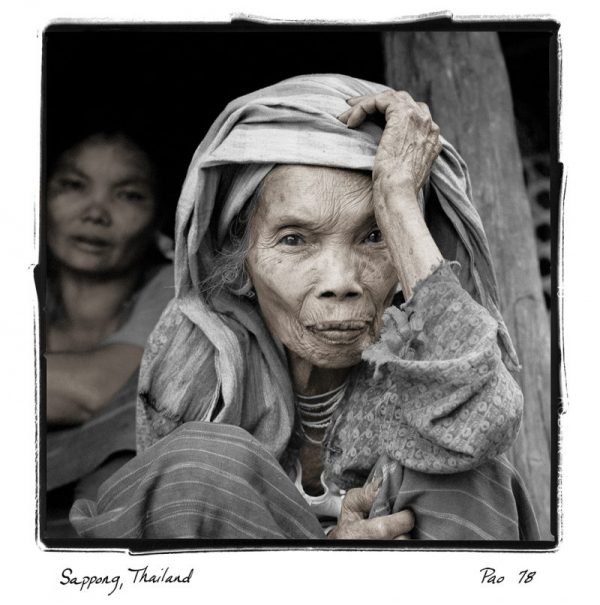

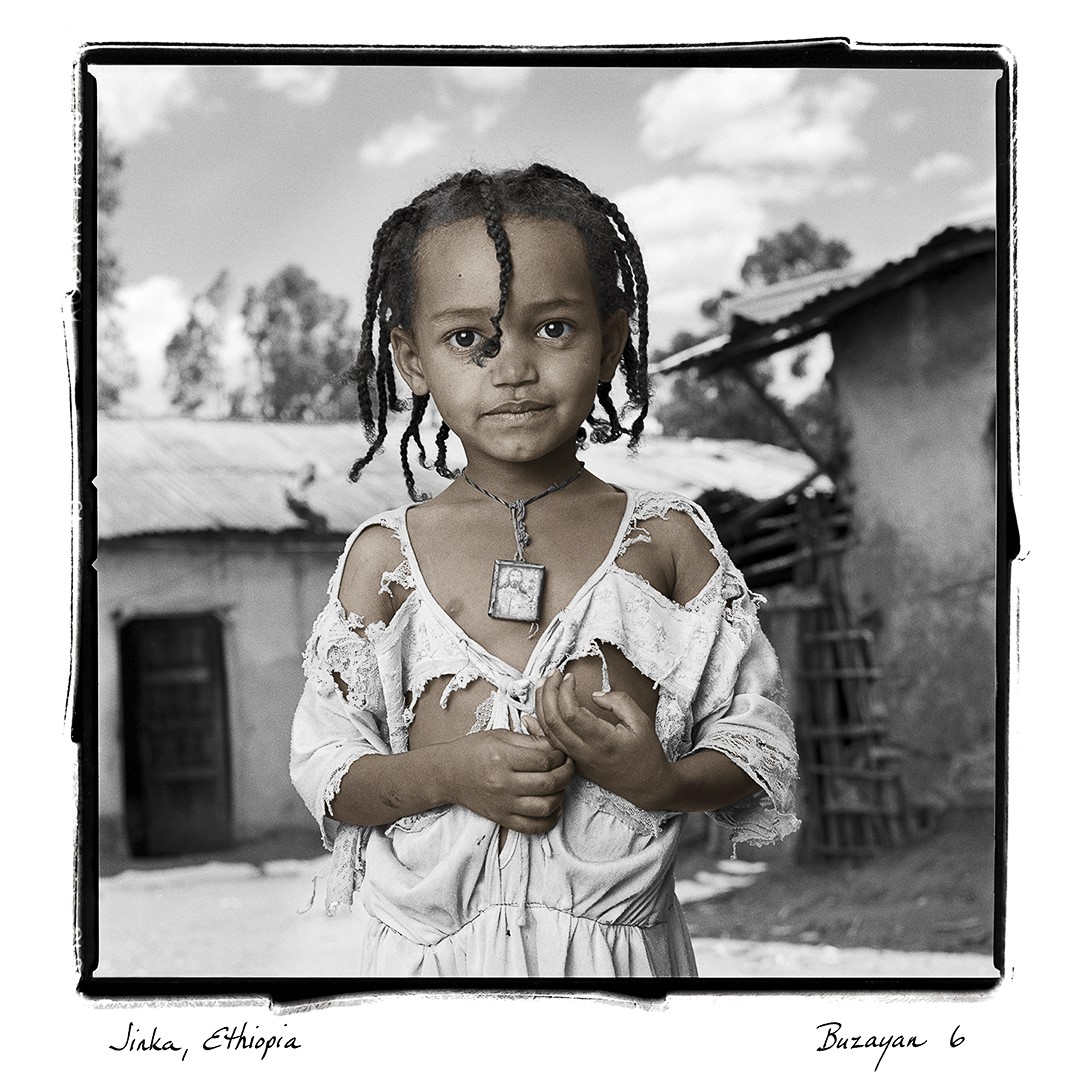

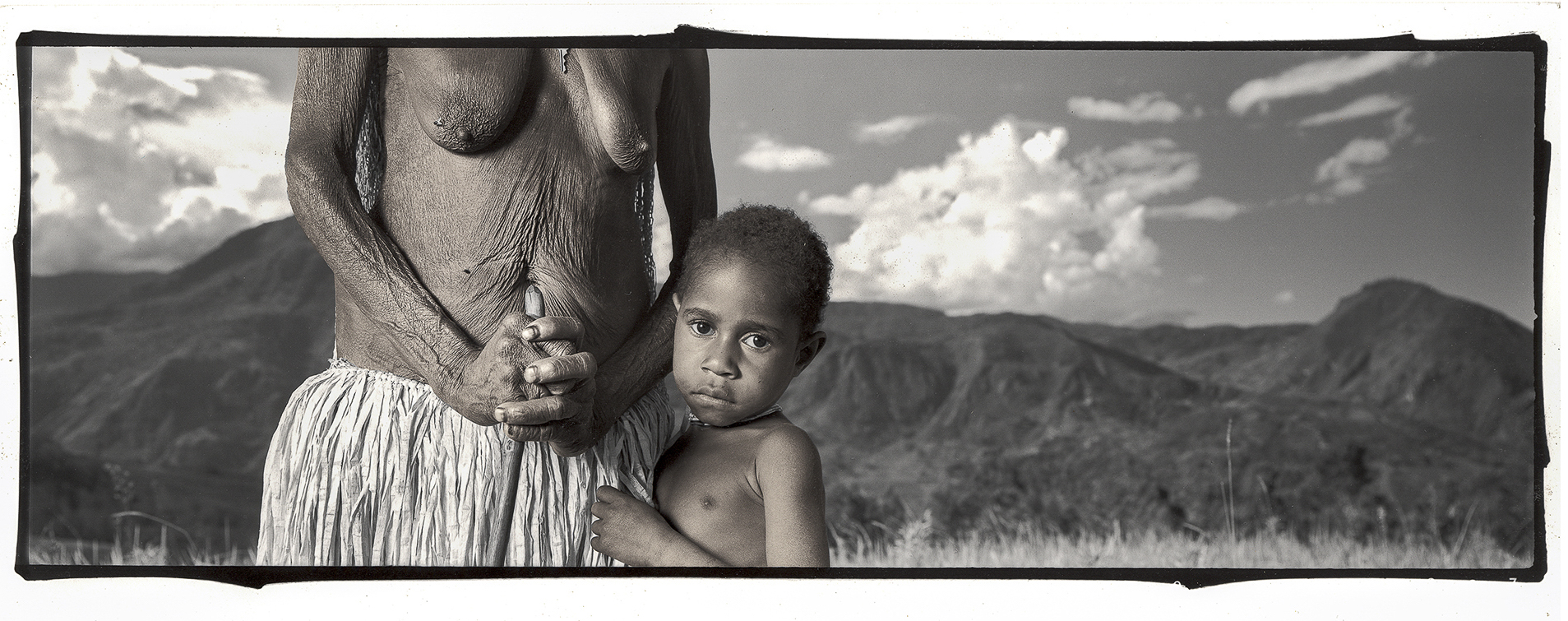

You have spent over a quarter of a century filming and photographing healers from various parts of the world. Is there something that they all have in common?

What makes them similar is that their identification as a healer follows some sort of a breakdown, usually in their youth. This may be an illness that led them to a near encounter with death, but usually they will have gone through an emotional crisis, which evoked fear. It is exactly at times like that that an older shaman, a person who has also experienced a crisis at an earlier stage in their life, needs to step into the process, to guide and teach the younger one. It is also noteworthy that most of these visionaries and healers hold common jobs. They may be housewives, or else they take their goats out to pasture. Most of them are not remunerated for healing. They usually do not care for its profitability, which makes them different from our health systems. They see their own talents as a gift to the community, for which they do not need to be paid. I remember an elderly woman-healer in Siberia. We spent a night camping next to her tent, and we gave her 30 dollars as a way of saying thank you. Next day she handed the money out to her patients.

Phil Borges – Photographer, Author, Filmmaker. For nearly three decades Phil Borges has been documenting indigenous and tribal cultures, striving to create an understanding of the challenges they face. His work is exhibited in museums and galleries worldwide. Phil has hosted television documentaries on indigenous cultures and shamanism for Discovery and National Geographic channels. He regularly presents at universities, teaches workshops, and has spoken at multiple TED events. Phil’s documentary film CRAZYWISE reveals a paradigm shift that’s changing the way Western culture defines and treats “mental illness”. After eight years and countless interviews with mental health care professionals, neuroscientists and individuals experiencing a mental health crisis, CRAZYWISE explores the deeper understandings of, and effective approaches to, a psychological crisis. The film highlights a survivor-led movement demanding more choices from a mental health care system in crisis.

Phil Borges was interviewed by Paweł Franczak.

If you want to learn more about shamanism and psychotherapy join our webinar “Where Shamanism and Psychotherapy meet” with Phil Borges, Ann Sinko, and Robert Falconer.